A New Vision for Embracing Queer Students’ Diverse Identities at HBCUs

By Joanie Harmon

April 7, 2025

Q&A with author Lori Patton Davis whose new book is a call to action and seminal resource for leaders and administrators at Historically Black Colleges and Universities.

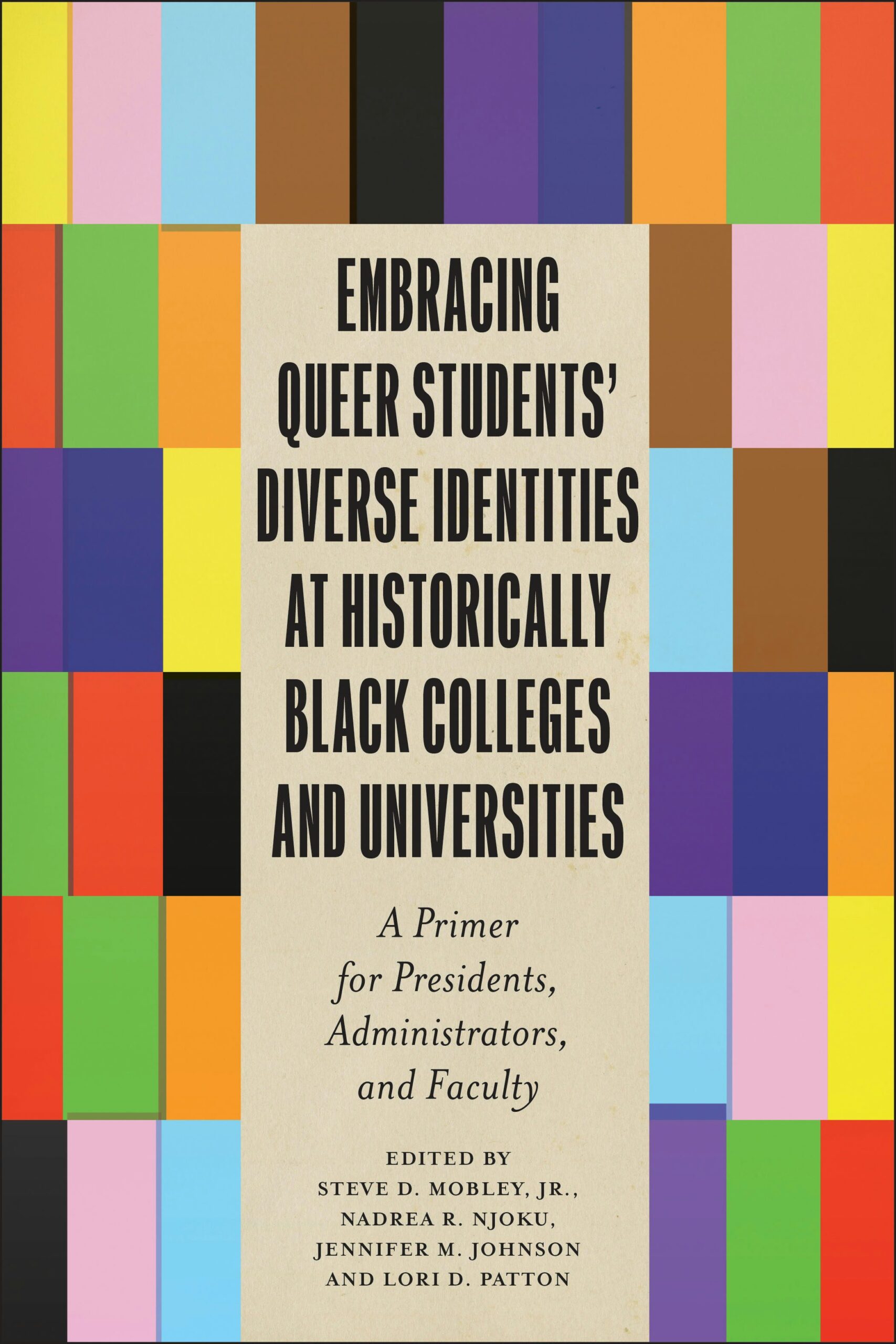

Lori Patton Davis has channeled her expertise as a higher education and student affairs professional and a researcher into creating scholarship that provides a vivid picture of what it is to be a Black LGBTQ college student. Her groundbreaking work is now the foundation for her co-edited volume, “Embracing Queer Students’ Diverse Identities at Historically Black Colleges and Universities: A Primer for Presidents, Administrators, and Faculty,” which was published by Rutgers University Press last fall.

Patton Davis is a UCLA professor of education and the Heyman Endowed Chair within the UCLA Department of Education and serves as faculty director of the UCLA Educational Leadership Program. She is best known for her research on the effects of race and racism in higher education; the intersectional experiences of Black girls and women in educational and social contexts; college student development; and the impact of campus diversity initiatives on student success.

The essays in “Embracing Queer Students’ Diverse Identities at Historically Black Colleges and Universities” explore the challenges and considerations of serving LGBTQ+ students within HBCU college and university settings, and summon these communities, higher education scholars, and scholar-practitioners to take thoughtful and urgent action to support and recognize LGBTQ+ students. Patton Davis’ groundbreaking work in this area is the underpinning of the book, which is written by HBCU presidents, faculty, administrators, alumni, and researchers, some of whom are her former students and colleagues.

Professor Patton Davis is a Fellow of the American Educational Research Association (AERA), a member of the National Academy of Education, and a senior scholar of ACPA—College Student Educators, International. Her numerous awards include the Pillar of the Profession from the NASPA—Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education; the George D. Kuh Award for Outstanding Contribution to Literature and/or Research from NASPA; and the Contribution to Knowledge Award from ACPA. She is a former president of the Association for the Study of Higher Education—the first Black woman to lead the organization—and a frequently-sought expert on various education topics, advising university presidents, senior administrators, philanthropic foundation executives, culture center directors, and educators in urban K–12 schools.

Professor Patton Davis earned her Ph.D. in higher education at Indiana University (IU); her M.A. in college student personnel at Bowling Green State University; and her B.S. in speech communication from Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville (SIUE).

UCLA Ed&IS: How did your experience as an administrator inspire and shape “Embracing Queer Students’ Diverse Identities”?

LORI PATTON DAVIS: Early in my career—I was an assistant professor at Iowa State—I received a grant from the American Psychological Foundation to study the experiences of lesbian, gay, and bisexual students at HBCUs. I didn’t attend an HBCU, but many of my friends who were part of my doctoral cohort at IU did, and they spoke so highly about their experiences, particularly in terms of cultural validation and developing Black identity. But in all those conversations, sexuality never emerged.

We studied student experiences, and everything I read at the time was about gay students at White institutions, nothing about HBCUs, and rarely anything about Black students. Black people aren’t a monolith. We aren’t all at White schools. We aren’t all heterosexual—there is great diversity among us. I went after the grant, and that strand of my research just took off. This would have been 2006 or 2007, and at that time, I was probably one of few in the field focusing on lesbian, gay, and bisexual students at HBCUs.

I began to publish, and the colleagues who are co-editors on this book are one generation after me in terms of being in the field, so they were reading my articles for their courses. Two of them went to HBCUs, one of them was my doctoral advisee at IU. I got to a point where I was publishing research articles, but a book was needed. I thought someone who identifies in terms of their sexuality [and] has attended an HBCU [should] lead it.

I approached Steve Mobley, now an associate professor at Morgan State University, and said, “Steve, I have a book idea. I know you have been doing this work. But we need a book out there, that centers these voices, and I would love it if you would lead it.” The rest is history. We invited Nadrea (Njoku), who was my doctoral advisee when I was on the faculty at Indiana University. Some of the same issues covered in our book came up in her dissertation findings. Jennifer Johnson at Temple University is a former employee of an HBCU who also began to look at these issues and write with Steve.

We are excited about the contribution this book makes. There isn’t another book like it—I think this will be the go-to guide for HBCU leaders and administrators. I’m extremely proud of my colleagues and [my] mentees, proud of the work that we were able to do in pulling together this book because it’s really excellent, and the essays by our contributors are amazing.

Ed&IS: How has the study of Black LGBTQ+ student experiences progressed since you began your research?

PATTON DAVIS: When I started doing this work, it was what would be considered an “open secret.” I believe it’s bell hooks and Cornel West’s book, “Breaking Bread,” where they talk about Black communities and this acknowledgement that there are LGBTQ+ folks within the Black community. It’s there, but we don’t really talk about it.

Early in my career, I found it very challenging to gain access to some HBCU campuses. There were some institutions I contacted, and they were like, “We don’t have gay students here.” These days, so much has changed where you have HBCU campuses that actually have LGTBQ+ centers and you see lavender graduations and other celebrations acknowledging LGTBQ+ students. The dialogue now is far more expansive and there has been a lot of progress, and I think that has a lot to do with more progressive [college and university] presidents, pressure from students, and the work of the Human Rights Campaign.

Ed&IS: How does your previous work in student affairs shape your current teaching in UCLA’s Department of Education?

PATTON DAVIS: I was an involved undergraduate at Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville. I did everything—student government, homecoming queen, sorority, you name it, which led to my master’s degree in student affairs at Bowling Green State University (BGSU). At BGSU, I had an opportunity to work in the office of multicultural affairs. That office was the key driver for how I understood what it meant to work with and support students of color.

Although I was involved [as an undergraduate student] and had a great experience, we didn’t have a culture center or a multicultural affairs office. But, at Bowling Green, to see the difference that office made for students shaped what I wanted to do in my career as a student affairs professional. My first job in student affairs was at Indiana State University as assistant director of student life. They had a Black culture center on campus, and I had an opportunity to connect with the director, to work with Black students, and to engage with Black alumni. Their connection with Indiana State was very much linked to the Black culture center and their engagement in Black sororities and fraternities, these specific enclaves in predominantly White environments.

Seeing all of this drove my ultimate goal of becoming a vice president of student affairs. My career was bouncing between being an administrator and wanting to be a student and be in the classroom. I decided to get a certificate in African American studies at Indiana State, and soon began a Ph.D. in higher education at Indiana University. I had a mentor in the higher ed program—Mary Howard Hamilton—who said, “You need to be a faculty member.” I taught with her, and she was like, “You have a gift. We need you—there aren’t enough Black women in the classroom.” She convinced me to consider a faculty route.

I did my dissertation on Black culture centers. I think it was the first dissertation on the topic. I wanted to look at the spaces that made Black students feel like they mattered on campus, whether it was a Black culture center, Black sororities and fraternities, multicultural affairs, a women’s center, or LGBTQ+ center. Looking at these spaces where a Black student could go and feel like they mattered ultimately shaped my research agenda as a faculty member and framed my teaching of courses that focus on campus diversity, student development, and race and racism.

Ed&IS: How do you hope to enhance education and training in the Educational Leadership Program (ELP) for leaders and administrators who will serve populations of color?

PATTON DAVIS: Coming to UCLA happened on the heels of being a department chair. This was one of the toughest roles of my career, and it felt like being a mini-dean because I led a huge department with 12 academic programs and a large faculty. I learned so much in the time I was chair and throughout other leadership roles. So, I’m hoping to impart some of the wisdom I’ve [gained] throughout those experiences.

I would love to offer courses that examine queer perspectives on leadership or on Black women or women of color in leadership. I’m excited about working with the students. I already have students I’m working with now on dissertations, and I’m looking forward to continuing to provide support and mentorship.

UCLA’s ELP program is known for producing wonderful leaders, particularly leaders of color, who understand the educational terrain and are committed to transforming education. I’m hoping to empower students, to increase the sense of belonging that already exists in the program. I want students, whether they’re working full-time or not, to detach themselves to this idea of imposter syndrome. I really want to play a role in helping them understand they’re not imposters at all—they’re exactly where they’re supposed to be.

Researching Alongside, for, and by Black, Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Communities at HBCUs

A Reflection

Lori D. Patton, Nadrea Njoku, and Jennifer M. Johnson

Excerpted from “Embracing Queer Students’ Diverse Identities at Historically Black College and Universities”

As this book has illustrated, Black Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer (GLBTQ) communities, not only exist at HBCUs, but also contribute to their greatness. In fact, HBCUs would not be where they are today without the presence of these communities in terms of leadership, creativity, innovation and the overall campus culture and identity.

Lessons Learned

Those interested in studying Black GLBTQ communities at HBCUs should acknowledge first and foremost that Blackness is not monolithic. In fact, HBCUs boast the most dynamic representations of Blackness, representations that encompass diversity of race, class, gender, religion, nationality, and sexuality. Thus, conducting this work requires letting go of preconceived notions of who attends HBCUs and what students’ experiences consist of in those spaces. With this information, “HBCUs must work toward creating a more inclusive and supportive campus environment … not only for [GLBTQ] students, but for students and staff seeking to express themselves on campus without fear of retribution” (Mobley & Johnson, 2015, p. 82).

Second, Black GLBTQ students, just like any population of students, will always be light years ahead of institutional change. In fact, they are the influencers of that change. By this, we mean that while some HBCUs are viewed as having conservative environments, this characteristic is also reflected in most postsecondary institutions. Colleges and universities writ large are strongly resistant to substantive change. Patton (2011) has noted that, “The reality is that few institutions have disseminated enough information to adequately educate members of the academic community about the experiences and needs of gay and bisexual students” (p. 78). Where HBCUs are concerned, the changes related to recognizing, validating, and supporting of Black GLBTQ students is now happening and will continue to make progress due to the work and labor that their students have been engaged in for decades. The rise of student activism across HBCU campuses is evidence that students are advocating for change. Black queer and trans* HBCU students are “demanding for HBCUs to openly embrace free and bold Blackness that is not stifled by antiquated notions …” (Mobley et al., 2021, p. 25). The strategies HBCU leaders use to respond to these demands will have lasting ramifications.

Third, researchers interested in GLBTQ populations should not assume that by nature of their identities, they need or even want support. Nor should they assume that the mere presence of support programs and resources will attract GLBTQ populations or meet their needs. Patton et al. (2020) explained, “For some, the presence of an organization would signal hypervisibility, which would be unwarranted if the goal was to make LGBQ students feel welcomed. For others, the presence of support services was at least appreciated and recognized even if the students were not involved” (p. 18). Institutions should not look to build a “one size fits all” approach to cultivating spaces of support. Rather, they should be open to students and staff creating and modifying their own communities with the support of rather than “approval” from the institution. Conversely, institutional leaders should be mindful of the costs associated with “queer student labor,” or the expectation that GLBTQ students will lead change efforts while pursuing their college degree. This arose in Nadrea’s (2017) work around Black womanhood with HBCU alumnae. A participant said of her continuum of experiences at HBCUs—first as a student and now as a tenure-track faculty member—that there is often a lone queer faculty member who shoulders the responsibility of mothering all the GLBTQ students.

Fourth, research related to Black GLBTQ groups must be done in community with and alongside them to center their voices in a collective desire to transform our HBCUs. So many histories of HBCU alumni have been lost due to the othering and erasure of the GLBTQ identity of the members of these groups. They have rich, illustrative stories and perspectives that are critical to the production of scholarship. They also have the capacity to write, engage in research design, data collection and so forth and where appropriate should have opportunities to write themselves into existence during the research process.

Last, but not least, in order for HBCUs to align with their founding missions, it is important for those in leadership and administrative roles to not only engage in decisions informed by the scholarship presented in this book and similar scholarship offered by other scholars but also to be thoughtful and committed to disrupting “heteronormativity, stringent gender roles, and … white supremacy” (Njoku et al., 2017, p. 783).

Conclusion

What is clear across our collective work is that we are scholars who deeply value HBCUs and part of valuing them is a desire to see them thrive, particularly in terms of GLBTQ populations. James Baldwin said, “I love America more than any other country in the world and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” Similarly, we love HBCUs more than any other type of postsecondary institution and it is for that reason that we remain committed to the act of critiquing, questioning and calling them to account in research and practice. Our hope is that this type of love will ensure the presence and representation of GLBTQ students, faculty, and leaders at HBCUs as well as policies, practices, and campus cultures that promote respect and humanity. Whether research is available to inform practice (or not), it is entirely possible for HBCUs to create services, outreach, and any other resources necessary to support GLBTQ students, hire GLBTQ administrators and leaders, and implement policies that regard GLBTQ people as whole and worthy humans.

Excerpted from “Embracing Queer Students’ Diverse Identities at Historically Black Colleges and Universities: A Primer for Presidents, Administrators, and Faculty,” edited by Steve D. Mobley, Jr., Nadrea R. Njoku, Jennifer M. Johnson, and Lori D. Patton. Copyright © 2024 by Rutgers University Press. Reprinted by permission of Rutgers University Press

Other articles in this issue

Jeannie Oakes: A Scholar Who Changed The World

Read more

A Jeannieology”: Jeannie Oakes’ Legacy Lives On in the Friends She Gathered

Read more

UCLA Pritzker Center for Strengthening Children and Families: Research, Practice, and Policy at Work

Read more

Sarah Bang on the Palisades Fire: Supporting L.A. Schools in Cris

Read more