A Jeannieology:

Jeannie Oakes’ Legacy Lives On in the Friends She Gathered

By John McDonald

April 7, 2025

If you talk with enough people about Jeannie Oakes, a few things happen. First, a common language begins to emerge. It’s a language rooted in words like equity, access, learning, opportunity, fairness, justice, community, democracy, and change. It also includes a commonly referenced list of terms people use to describe her. Words like listener, learner, leader, scholar, teacher. And others, such as curious, kind, caring, humble, compassionate, courageous, rigorous, strategic, persistent, and hard-working. Maybe most importantly, friend, mother, grandmother, wife.

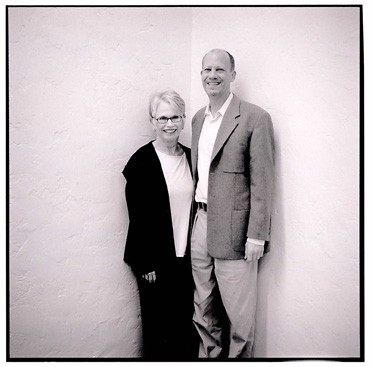

“She was a devoted, smart mom, grandmother, and wife. I would want people to know that,” says her husband, Martin Lipton.

As you talk with people, you become aware of a large, informal network, a “Jeannieology” of sorts, connecting people across the field of education and beyond. “People joke about six degrees of separation from the actor Kevin Bacon,” says Sophie Fanelli, president of the Stuart Foundation, who also worked with Jeannie at UCLA Institute for Democracy, Education, and Access (IDEA). “With Jeannie, it was two degrees of separation. I don’t know anyone who’s had this kind of impact on people, on all of us, weaving this web of connections.”

Jeannie was a collaborator and a collector and connector of people and friends. In the process she cast a wide net, weaving a fabric of sorts, stretching across multiple generations, linking people across ideas, issues, research, projects, programs, practice, policy, and political battles.

“We are a collection of unusual suspects,” says Annamarie Francois, associate dean of public engagement at UCLA Ed&IS.

The other thing that becomes clear is that among these friends and family who make up this community, there is a deep well of love and affection for her. They are grieving, they miss her.

“It brought me great solace to know that I could message Jeannie and say, ‘let’s get on Zoom, I have questions for you,’” says Marisa Saunders of the UCLA Center for Community Schooling, fighting back the tears in her eyes. “It just was always so reassuring to know that I could ask, ‘Are we going down the right path here?’ That brought me and others a whole lot of comfort.”

In the months following Jeannie’s death, in a political moment when much of what she and many others have worked toward and cared about appears to be at risk, almost to a person, people in this community are asking some form of the question, “What would Jeannie do?”

But as Robert Cooper, UCLA professor of education, says, “A real legacy is something that endures throughout time. She was so prolific in her writing and in the way she touched the lives of so many people that you can always know what Jeannie would do. You just have to ask someone. They can tell you.”

A Commitment to Social Justice

“Jeannie really was an equity warrior, in the sense of never giving up, of having the stamina, of having the determination,” says Linda Darling-Hammond of the Learning Policy Institute. “She knew this was hard work, two steps forward and one step back. There’s always going to be pushback. You have to have people who can see the long haul and help others stay focused and stay committed and moving forward. And of all the other wonderful traits of Jeannie’s, that was one of her superpowers. She would say to others, ‘Don’t give up; take the next step; be strategic. Think about what’s next.’”

Throughout her career, Oakes remained steadfastly focused on equity, on the pursuit of social justice, on changing a practice and system of education she saw as deeply inequitable and unfair. It drove her; it was central to her being.

“It was always very clear to me that for Jeannie, education was the cornerstone of democracy and justice,” says Fanelli. “Her commitment to justice was what drove so much of her research.”

“She put the social justice up front, overtly saying, ‘this is what we should be doing,’ trying to convince the rest of us that it’s the right thing to do,” adds Kevin Welner, a professor at the University of Colorado Boulder School of Education and the director of the National Education Policy Center (NEPC). “She demonstrated to me and other students that excellent research and a commitment to social justice can go hand in hand.”

A Commitment to Change

To Making Things Better

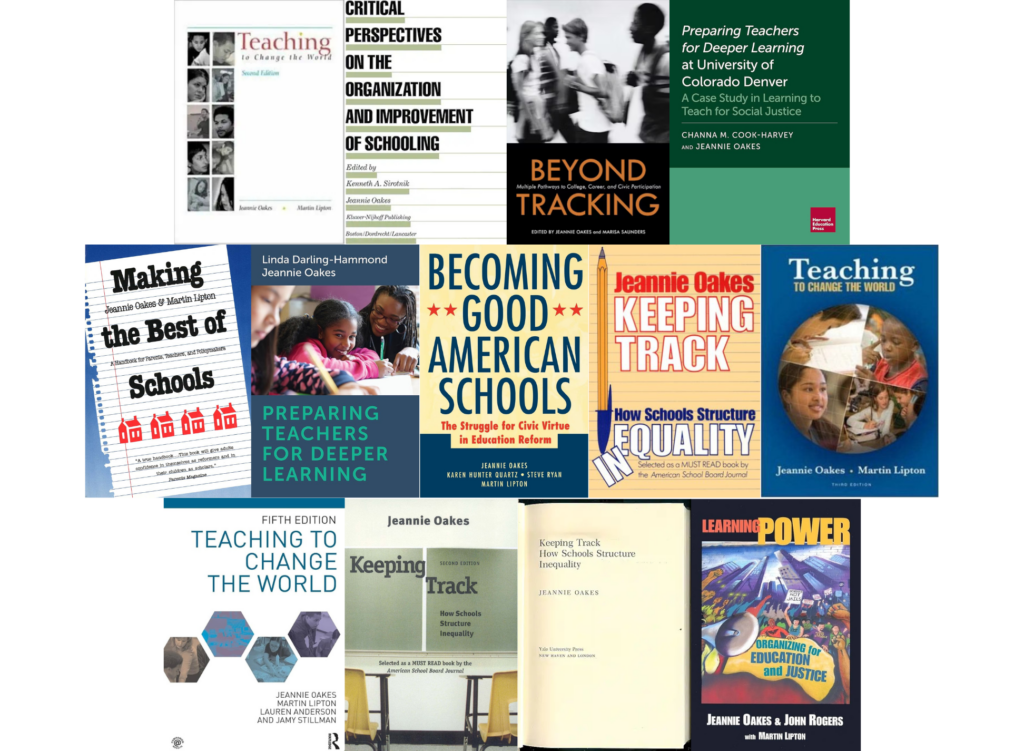

“If you glance down in one quick swoop at [Jeannie’s] publications, pay attention to the titles,” says Lipton. “‘Keeping Track,’ ‘Teaching to Change the World,’ ‘Becoming Good American Schools.’ These are verbal descriptions of actions. These are about doing. She wanted to change things.”

“She studied things in order to change them, to make them better,” says Karen Hunter Quartz, director of the UCLA Center for Community Schooling. “Jeannie helped me and many others to see that that’s the point. It’s not that you’re not going to be careful, you’re not going to weigh evidence, you’re not going to be systematic—you’re going to be all those things. But why are you doing it? You’re doing it to change something, so own it, lean into it, and figure out how to make it change. That’s what you learn from Jeannie. You learn that you can change the world.”

A Side-by-Side Leader

“She was a ‘side-by-side’ mentor and leader,” says Megan Franke of UCLA Center X. “It was never, ‘I’ll do it; you come along.’ It was, ‘Let’s do it together.’”

“Jeannie had this incredible ability to identify diamonds in the rough, to identify possibility, so to speak,” adds Francois. “She saw possibility and used whatever time, talent, and treasure she had to help folks come into their own. It was her interaction with people and making them believe that they could do this hard work that made the difference.”

“Jeannie never wanted to be at the front or have the microphone. She was always looking to partner. She was always validating us in such a positive way,” says Veronica Melvin of the LA Promise Fund. “Every time someone spoke, she would thank them for their contributions. She would comment about how valuable their contribution was in a lovely way that just made the individual feel really good about what they were saying. I loved that she would say, ‘That’s brilliant.’”

“She was always at the table as a partner,” adds Saunders. “She respected the wisdom in the room. She did not for a second think that she had all of the answers.”

Other articles in this issue

Jeannie Oakes: A Scholar Who Changed The World

Read more

UCLA Pritzker Center for Strengthening Children and Families: Research, Practice, and Policy at Work

Read more

A New Vision for Embracing Queer Students’ Diverse Identities at HBCUs

Q&A with Lori Patton Davis and Book Excerpt

Read more

Sarah Bang on the Palisades Fire: Supporting L.A. Schools in Cris

Read more