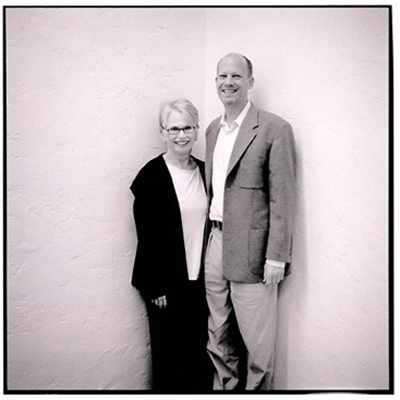

Jeannie Oakes:

A Scholar Who Changed the World

By John McDonald

April 7, 2025

Jeannie Oakes was a UCLA presidential professor emerita in educational equity at the UCLA School of Education and Information Studies. She authored 17 scholarly books and more than 100 published research reports, chapters, and articles, including the groundbreaking 1985 book “Keeping Track: How Schools Structure Inequality.” The book provided clear evidence of the systemic difference in learning tracks in American middle and high schools and its implications for learning that fueled a decades-long battle against the tracking of students. “Keeping Track” would be published multiple times and named one of 60 “Books of the Century” by the University of South Carolina Museum of Education for its influence on American education. A member of the National Academy of Education, Oakes would earn many awards for her research and scholarship, including the Lifetime Achievement Award from the California Educational Research Association and three major awards from the American Educational Research Association (AERA), including the 2001 Outstanding Book Award for “Becoming Good American Schools: The Struggle for Civic Virtue in Education Reform.”

The marshaling of powerful data and research would be fundamental to Oakes’ career, to make her case and advance her cause in educational equity.

“Fundamentally, Jeannie was a shy person. She described herself as an introvert,” says her husband of 41 years, Martin Lipton. “But she was enormously curious and activist-minded, and she found confidence in hard work and preparation. The work began with Jeannie’s gut, her quiet outrage about what she saw as unfair. But then she had to find out about it. She had to do the research; she had to get the data. It was not just a matter of speaking out against unfairness. You had to come with the goods.”

Oakes’ work would reach far beyond the usual teaching, research, and publishing of academia.

“She changed what it meant to be a scholar,” says Megan Franke, UCLA professor of education and faculty director of UCLA Center X.

Oakes touched the lives of countless people, building a network of friends and colleagues across public education, academia and state and national policymakers, civil rights leaders, community advocates, philanthropists, and others engaged in the quest for the pursuit of equity and social justice for students too often denied its grace.

“Jeannie inspired multiple generations of people to center justice in their work,” says Michelle Renée Valladares, associate director of the National Education Policy Council (NEPC). “Whether it was the work of research, teacher education, education litigation, public scholarship, philanthropy, public policy—wherever she went, she inspired people that they could and do have a moral responsibility to be their best self and live justice all the time, not just when it’s convenient. That’s her legacy.”

It is a legacy of consequence.

“There are millions of children in California and throughout the country who’ve never heard of Jeannie Oakes, but for whom she made a difference in terms of them getting an education and being able to pursue their dreams,” says Mark Rosenbaum, a longtime civil rights attorney who worked with Oakes on education and civil rights litigation. “The fact that low-income kids have books in their classrooms, that they have qualified teachers, that they have decent facilities and opportunities that approach those of other students of more affluent circumstances, is due in great part to her. She narrowed the difference between the haves and the have-nots and gave those kids a fighting chance.”

After graduating from San Diego State and obtaining a master’s degree in American Studies at California State University, Los Angeles, Oakes got her start in education teaching middle and high school English in Los Angeles. Eventually she would go on to earn a Ph.D. in education at UCLA in 1980, beginning a meteoric academic career fueled by her indignation at the inequities she saw in schools and her own insatiable quest for learning.

“Jeannie was an excellent observer, and if you’re a teacher with a conscience and are paying attention, you see inequality smacking you in the face every day and affecting the lives of the kids. I think she observed that,” says Linda Darling-Hammond, president and CEO of the Learning Policy Institute.

Oakes remained at UCLA for five years, conducting research with John Goodlad, dean of the then-UCLA Graduate School of Education, for his groundbreaking work, “A Study of Schooling.” In 1985, she joined RAND as a senior researcher, beginning a lifelong friendship and working relationship with Darling-Hammond, her supervisor at the noted think tank. At RAND, Oakes would publish her seminal work, “Keeping Track.” In 1989, she returned to UCLA as a tenured professor of education, a move that would have a transformative impact on her career, the university, and the lives of so many who studied and worked there.

“Her work and thinking forged a bright, brilliant arc that shaped our school and even now helps to guide our future,” says Christina Christie, Wasserman Dean of the UCLA School of Education and Information Studies. “She was a well-recognized scholar who was able to push up against folks with very strong disciplinary identities to say, ‘This is where your identity needs to be, it needs to be around justice, equity, diversity, and what we too often leave out, democracy.’”

A Teacher, Mentor, and Friend

At UCLA, Oakes touched the lives of hundreds if not thousands of students and colleagues, furthering learning, transforming careers, and building friendships that would last a lifetime. She served as a formal advisor to more than 70 students in UCLA’s graduate and professional programs in education and informally to countless others.

“She taught me to be a scholar,” says UCLA Professor of Education Robert Cooper, who may have been Oakes’ first graduate advisee. “As a professor, an advisor, and a researcher, much of what I do, I realize now, is patterned after what I saw and what I experienced from her. When I work with graduate students, I am trying to connect with them as people. I am trying to understand how they want to use their work to further their cause and to help them understand the ‘why’ of why they’re engaged in this work. Because this equity work, the social justice work, is not easy.”

As a new faculty member, Megan Franke remembers Oakes’ friendship and guidance as transformative.

“She took me under her wing; she was my mentor. She edited the paper that probably got me tenure, and she gave me harsh feedback on it. She said, ‘Hey, you have got some work to do here,’ and then she helped guide me through that revision process. She helped me navigate what it meant to be a professor. She shaped my career.”

At UCLA, Oakes’ work would evolve from traditional research and publishing to the collaborative building of programs to strengthen teaching and schools and complex initiatives to engage the public and address policy. Key milestones included the development of Center X, UCLA Institute for Democracy, Education, and Access (IDEA), and UC/ACCORD, the University of California All Campus Consortium on Research for Diversity.

UCLA Center X: The Power of Many

In 1992, in the aftermath of fires and destruction stemming from anger at the not-guilty verdict in the Rodney King police brutality case Oakes and others at UCLA grew increasingly concerned they were not doing enough to support students and schools in the neighborhoods of Los Angeles that faced the greatest challenges.

Oakes said that she was, “struck by the notion that something was very wrong. Almost none of us was doing anything meaningful about Los Angeles. And we needed to be doing something.”

That something would turn out to be the development of UCLA Center X, a program of educator preparation that aims to develop teachers to “change the world.”

Over the next three years, Oakes would meet with K–12 educators, colleagues at UCLA and across academia, community members, and others to learn about the wants and needs of educators and students in some of the most challenged neighborhoods of Los Angeles. Together, they developed a transformative program of educator preparation and support to meet those needs.

“People would say, ‘Yes, we need to have these equitable educational systems,’ but nobody ever really did anything about it. Jeannie made the work real,” says Jody Priselac, retired associate dean for community programs at UCLA, who worked with Oakes on the planning of Center X and who would eventually become its director.

“Every Friday afternoon for a few hours, we would get together and talk about what it means to educate and prepare teachers. It was the way that she asked questions that got us to think deeper about what it would look like. It was her questions, her listening. We just kept getting closer and closer to the creation of this teacher education program that was focused on social justice, that was about building communities, that knows that the K–12 community is valuable and has something important to say,” says Priselac.

“The program was very intentional and very explicit in what they were trying to do. They were trying to create a pipeline of educators that were steeped in social justice theory and practices into underserved schools,” says Cicely Bingener, who was in the first teacher training cohort of UCLA Center X in 1995, has spent her career teaching in the Inglewood Unified School District.

“When I look at UCLA now, that is what I see. I see a commitment to equity, to social justice, to diversity, and to democracy. And I think that grows out of Center X.”

In Oakes’ 1996 paper on the development of Center X, “Making the Rhetoric Real,” one of the topic headlines is “The Power of Many.” In it, she describes bringing together disparate elements of the UCLA Department of Education under one mission and organizational umbrella in support of the newly formed Center X: the Teacher Education Program, the Ed.D. program in Educational Leadership, six of the California Subject Matter Projects and other professional development projects for practicing educators. These programs “were formerly quite separate,” Oakes wrote, “and it has dramatically changed the nature of those activities.”

The project brought together people from different backgrounds with different skills and expertise. The effort engaged junior and senior faculty members, practicing K–12 professionals, staff researchers, graduate students, teaching candidates, future school leaders, and others to create Center X. They represented a range of ages, ethnicities and sexual orientations. Some spoke only English, but many also spoke Spanish.

Thirty years later, UCLA Center X is nationally recognized for its groundbreaking efforts to prepare and sustain educators focused on social justice. The rhetoric became real. The phrase, “the power of many” may have originally been written about Center X, but today, it stands as a cornerstone of Oakes’ work.

“To me, Center X epitomizes what she believed in and what our role [in our communities] should be. That was her work,” says Priselac.

“She was a collaborative thinker and actor who was always trying to build what in effect was a movement for social change, a movement that connected educational researchers with legal advocates, with grassroots organizers, with young people and parents,” says John Rogers, UCLA professor of education and director of IDEA. “She saw her great skill as bringing together people who had extraordinary capabilities. She was always trying to create teams that could do important work.”

UCLA Institute of Democracy, Education and Access (IDEA)

In 2000, in a new initiative that would expand the definition of public scholarship, Oakes partnered with Rogers to form UCLA Institute for Democracy, Education, and Access (IDEA). The intent was to bring together a wide range of people across Los Angeles to address critical problems confronting public education.

“At the time, conditions in California public schools were at a low point. Schools were so overcrowded, there was such a shortage of teachers, and many schools lacked needed resources, particularly in low-income neighborhoods,” Rogers says. “Jeannie and I had the sense that a narrow focus on school reform was only going to go so far—broader changes and broader alliances outside of the educational sector were needed.”

IDEA connected educators in conversation with civil rights activists, legal advocates, community organizers, and others who had skills in moving legislation. IDEA faculty, postdoctoral scholars, staff, and graduate students partnered with young people, parents, teachers, and grassroots organizations to conduct and share research on the conditions of education, providing data and analyses on specific challenges and forging connections among members of grassroots groups, journalists, researchers, and policymakers.

“In effect, we were trying to build a movement for social change,” Rogers says.

One important partnership was with community organizers working to make the A–G courses required for entrance into a CSU or UC campus available to all students in the Los Angeles Unified School District.

“Jeannie and John and others at IDEA shared data and analysis with us to inform our campaign,” says Veronica Melvin, president of the LA Promise Fund, who was then working for the Alliance for Better Communities. “We quickly realized how powerful it was and how powerful the combination of community action and evidence-based research could be.

“Jeannie made our campaign stronger and smarter through the infusion of data merging with community experience, but she also joined in the advocacy that went along with it. She was at all of our rallies and marches and was beloved by our community members.”

At IDEA, Oakes also got involved in civil rights litigation seeking to ensure students’ equitable access to educational resources needed for success in school and learning.

In Williams v. State of California, which challenged the constitutionality of the state’s education system and contended that California was unfairly denying adequate resources for educational success to some students while providing them to others, Oakes and her UCLA colleagues, including Professors of Education and Co-directors of the Civil Rights Project, Gary Orfield and Patricia Gándara, would convene education experts and develop a set of reports analyzing and challenging the defendants’ claims. Their research made clear the need for California students to have access to basic requirements for educational quality and opportunity and the implications of the lack of these resources for educational outcomes. Oakes would testify for 16 days. The lawsuit was settled in 2004, with California agreeing to increase funding by almost a billion dollars and establishing minimum standards for educational resources for students.

“There had never been a case using the California constitution to challenge the statewide school system, and Jeannie didn’t hesitate for a nanosecond,” says Mark Rosenbaum, who was the ACLU lawyer on the case. “If you want to know who the lead lawyer on the case was, it was Jeannie Oakes. She developed the theories, she developed the strategies, she built the team of the leading experts in the country.”

UC/ACCORD

In the wake of the passage in 1996 of California’s Proposition 209 prohibiting state entities from using race, ethnicity, or sex as criteria in public employment, public contracting, and public education, Oakes would again expand her portfolio, serving as founding director of the University of California All Campus Consortium on Research for Diversity (UC/ACCORD) in 1998.

UC/ACCORD provided research fellowships and hosted meetings at the UCLA Lake Arrowhead Center, engaging researchers and students, as well as policymakers, teachers, and others, in research and discussion about equitable education policy, practices, and strategies to increase college preparation, access, and retention.

“She mentored almost all these young scholars as part of a family, an intellectual community, a family of folks,” says UCLA Professor of Education Daniel G. Solórzano, who joined Oakes as co-director of UC/ACCORD, and would later become director.

“It was amazing because you got to see people who are committed to these issues engaged in ways that show that commitment to people, to communities and people. We saw ourselves as a family. We even talked about family in these spaces. I still feel a part of that family and Jeannie was a part of that.

“And one thing you need to know about Jeannie, she was a committed sister,” says Solórzano. “She really was committed to equity issues, and she put her commitments to action. That’s what I loved about working with her.”

“The meetings that Jeannie convened for UC/ACCORD were serious, focused, and a lot of fun,” says Max Espinoza, who participated as a legislative staffer and is now a senior program officer for the Gates Foundation. “They were joyful, even though some of the issues we were discussing were really hard. It was a special space she created for us. And she was always clear, particularly with regard to the University of California or public schools and universities in general, that we can have excellence and equality at the same time. It wasn’t a choice between these ideas.

“UC/ACCORD is a perfect example of Jeannie always trying to ensure that the research was connected to and utilized by the people that needed it most—the community, educators, policymakers,” Espinoza adds. “It wasn’t enough to be a brilliant academic if the research did not get to the people who needed it. At the same time, she was also building a pipeline of future scholars and teaching them in the process how to make sure their research was relevant to the people who would eventually need to utilize it to make change.”

Next Steps in the Quest for Equity

In 2008, Oakes left UCLA to join the Ford Foundation as director of educational equity and scholarship.

“The etymology of philanthropy is the love of humanity. Who embodied that more than Jeannie Oakes?” asks Sanjiv Rao, who worked with her as an education program officer at the Ford Foundation and now works at the Democracy Fund.

At Ford, building on a term coined by her husband Martin Lipton, Oakes would lead the “More and Better Learning Time” initiative. The “more” was about equity, and the “better” was about excellence. The initiative aimed to transform education by providing students whose lives had been affected by poverty with access to both. The program provided grants to community organizations, school districts, and others in support of strategies to increase learning time for students, expand professional development and collaboration time for teachers, and support student access to high-quality enrichment and career preparation programs.

The initiative operated in six cities across five states. Los Angeles was one of those cities, and the effort would bring Oakes back to the community, where she would work with Hewlett Foundation education officer Peter Rivera, who was then a program officer at the California Community Foundation, and with others in the neighborhoods of Los Angeles.

“When she showed up at a meeting, you didn’t feel her presence as ‘Jeannie Oakes.’” says Rivera. “You felt her presence as someone saying, ‘Let’s think together on some of these things; tell me what the problems are, I’m listening.’

“A lot of folks in philanthropy just think they can plop into places or communities and share these silver bullets around. They bring ideas on how they are going to change things, and they pour a lot of money into it, and they don’t build any community around anything, and a lot of it just flops,” says Rivera. “What was most enjoyable about working with Jeannie and her team was the recognition they weren’t just going to show up as the Ford Foundation and do this work in places without engaging people and having conversations and being in dialogue around what people had, and wanted, and needed.”

Oakes’ work had a transformative impact on the field of philanthropy. She was an active participant in the Education Funder Strategy Group, a network of donors across a group of about 30 foundations focused on national education policy. She also played an important role in the Partnership for the Future of Learning, encouraging the organization toward new ways of thinking and pushing to expand participation and include more people from academia and other sectors.

“Jeannie could see the power of foundations and how to help staff in foundations become better at their job by learning and being part of conversations,” says Sophie Fanelli, president of the Stuart Foundation. “She was always asking, what happens beyond that first grant? How do we make sure it leads to systemic change, that it’s about justice. I can’t think of any education foundation that hasn’t benefited from Jeannie’s work as a scholar. At the Ford Foundation she really worked in partnership with other foundations.”

A Push for Community Schools

Oakes had a great influence on the development of UCLA Community School in the Pico-Union neighborhood, which opened in 2009, and later the work by the UCLA Center for Community Schooling.

“The foundations of our work in community schools are a result of that legacy,” says Annamarie Francois, associate dean for public engagement at the UCLA School of Education and Information Studies and former director of Center X.

“Our community school is the bringing together of professional practitioners, and researchers guided by beliefs around social justice. To me, that was the foundation of her work,” says Priselac. “It was the importance of giving a voice to all the stakeholders who are typically left out. In those early meetings to create the UCLA Community School, everybody was there. There were parents, there were kids. There were union reps, teachers, school and district administrators, university professors and staff, graduate students, and more.”

In 2017, Oakes would join the Learning Policy Institute to pursue educational research with an aim toward impacting policy, particularly around community schooling.

There, she would join with colleagues to research and publish “Community Schools as an Effective School Improvement Strategy: A Review of the Evidence,” which synthesizes the findings of 143 rigorous research studies on the impact of community schools on student and school outcomes. The report provides important information for school, community, district, and state leaders as they consider community schools as a strategy for providing equitable, high-quality education to all young people. It establishes four pillars of community schools: integrated student supports, expanded and enriched learning time and opportunities, active family and community engagement, and collaborative leadership and practices. Today, those pillars are a critical piece of the state of California’s framework for the establishment of community schools.

The Practice of Public Scholarship

Oakes agreed to serve as the president of AERA during its centennial year. During her tenure, she would place public scholarship at the forefront of her efforts. In her presidential address at the 2016 annual meeting, “Public Scholarship: Education Research for a Diverse Democracy,” she encouraged the association’s members to play a larger role as public scholars, acting to “bring education research out of the weeds of scholarly journals and into the public sphere.” Citing John Dewey, she said, “I believe there is enormous potential for education researchers to contribute to the ‘hurly-burly’ of education policymaking: to teach and to inform the political process.” She believed public scholars “should produce and use knowledge that supports the cultural and political shifts that inclusive and equitable education requires.”

“She taught me that we can’t just sit in our academic journals,” says Karen Hunter Quartz, one of Jeannie’s first graduate students, who now leads the UCLA Center for Community Schooling. “She would always say, ‘Yes, do great, careful work, but don’t leave it there. Don’t leave it there, because it’s too important.’”

Oakes saw public scholarship as a two-way street. She used it not only to share information to advance equity but to further knowledge and learning. She wrote that public scholars, “should not only reject the idea that collaboration and strong relationships with the public might compromise research rigor—they argue that it is often required for research to be fully informed.”

And she shared what she learned with those who could help to make a difference.

“Jeannie took the idea of public scholarship into the community and said, ‘We need to be working with community organizations, with grassroots groups and community activists,’” says Kevin Welner, one Oakes’ graduate students and now a professor at the University of Colorado Boulder School of Education and the director of the National Education Policy Center (NEPC).

“These activists,” Jeannie wrote in “Learning Power” (a book co-authored with Rogers), “with good data in their hands, changed what was thought to be ‘reasonable’ and politically possible.”

“Jeannie understood what powerful research was,” says Marisa Saunders, associate director of research at the UCLA Center for Community Schooling. “It’s not that journal article that you published and sits on somebody’s bookshelf. It is the research that can make change. It is the public scholarship that comes from the ground up, responding to questions that come from students, families, and communities to make the changes they need. That is what she valued.”

A Lasting Legacy

Jeannie Oakes leaves behind a legacy of significant research and accomplishment.

“We owe a great debt to Jeannie Oakes,” concludes Francois. “Jeannie changed the world by seeing, caring about, and preparing a generation of scholars and practitioners with the knowledge, skills, and disposition to make educational equity and justice a reality for all kids. We are her legacy. I don’t ever want us to forget that this really smart, kind, caring White woman, who did not have to go where she did, did what she did. As she has written, she cared enough to do the little things that she could do and to encourage and inspire those around her to do the same. Not [to do it] in the way that she did it, but to engage in the struggle. And that’s the first step, right? To engage in the struggle.”

Other articles in this issue

A Jeannieology”: Jeannie Oakes’ Legacy Lives On in the Friends She Gathered

Read more

UCLA Pritzker Center for Strengthening Children and Families: Research, Practice, and Policy at Work

Read more

A New Vision for Embracing Queer Students’ Diverse Identities at HBCUs

Q&A with Lori Patton Davis and Book Excerpt

Read more

Sarah Bang on the Palisades Fire: Supporting L.A. Schools in Cris

Read more